When she turned 18, her father registered a company in her name. That’s just how things are in the Nutti family.

“While I was growing up, I noticed that people were always working. For me, work is a natural, everyday part of life. Just doing. When you sit around the fire and tell stories or, nowadays, when you’re watching Netflix, your hands are always busy. I think there is some kind of mindfulness in allowing your hands to be occupied with art craftwork.”

Leila had seen her mother and grandmother busy with duodji, Sámi craftwork. They were making pewter-embroidered leather bracelets and handbags that would be sold at markets. And she had seen her father fixing something that was broken or crafting something new, or deliberating with her mother about what must be done with the reindeer. Always the reindeer. Although so much else can be said about the Sámi culture and way of life, reindeer are never far from discussion.

When we decided to meet for this interview, I suggested a date. Leila replied that it would probably work for her, provided it wasn’t during the season when the reindeer must be separated from the herd.

Arctic design

Not only a reindeer owner and painter, but she is also a craft artist and has written a book about reindeer herding with dogs. This, in turn, has attracted tourists, who come to learn about the latter. In addition, Leila co-manages a project to promote Arctic design throughout the world. When we meet at the Ájtte Museum in Jokkmokk, it is snowing heavily, and she has just returned from New York. As part of the project, together with several other designers from Norrbotten and Västerbotten, she has attended a seminar and an exhibition of the group’s work.

“It’s an incredibly exciting project to work with. With us in New York were Care of Gerd, a producer of skincare products, Hikki, who makes supercool outdoor bathtubs, and the Sámi glass artist Monica L. Edmondson. There is such an incredible range in a project like this, as well as in our designs. And it’s not just Sámi things, but more about what the northernmost part of Sweden has to offer. The intention is that about 50 companies from the north will have the chance to attend these shows throughout the world. First up was a visit to Copenhagen, and then New York. The next one will be in Paris, followed by Toronto, and then Tokyo.”

The difference between Tokyo and Eanonjálmme, where Leila’s reindeer graze during the summer in Sweden’s largest Sámi village, Sirges, couldn’t be more striking.

“I couldn’t agree more. Tokyo is an entirely different world. And new technology has made the world a completely different place.”

Home in two worlds

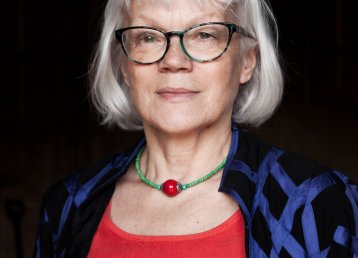

Leila Nutti, born in 1991, is somehow at home in a time that no longer exists. When she concluded her studies at the Sámi college, Samij Åhpadusguovdásj, in Jokkmokk, she made an item in woven roots, sewed a coat from the pelt of a reindeer calf and fashioned a gietka, or crib. At the same time, she has all the social media she needs to be present in the digital marketplace.

“That’s so strange. If I could choose, I wouldn’t live in the digital world at all. But that’s impossible since I run a company, or because that’s just how things are. The implication is that I sometimes know more about what’s happening in American politics than I do about what is really important to me. Will it be a good grazing winter for my reindeer, or not?”

Everyone in her family works with reindeer. Her parents are still active. Her older sister has scaled down a bit since starting a family, so her younger brother is now the one who is most often out freezing on a snowmobile. That’s family life among the Sámi; everyone helps out when and however they can.

“During certain periods, reindeer are the only concern. When it’s time to work with the herd, you can’t simply say, ‘Sorry, I have a meeting.’ It would be irresponsible to book a meeting at the wrong time.”

Family heritage

Leila sees herself as more of a painter than a craft artist. The artistic streak is part of her family heritage. Lars J:son Nutti was her father’s uncle. As we wander through Ájtte, we pause to admire a gigantic work by the famous artist. At first, it looks rather abstract. And, certainly, it is abstract and very colourful, but amid the profusion of colours appear various more or less detailed images. I stand eye-to-eye with a beast that seems to be hiding in the painting.

“It might be some kind of gufihttarat,” says Leila, smiling. “The Sámi culture has always been very didactic. Parents frighten their children by saying that, if they poke a stick in the fire, their reindeer calves will go blind. Of course, no one wants to blind the calves; we love our animals, but it was really just a way to prevent sparks from flying out and starting a fire in the hut or tent. I sort of miss that these days. Now, we just give the kids a tablet to play with, so they don’t play with fire or wander off into the woods.”

Her paintings are inspired by the Sámi lifestyle and the environment that surrounds her. She wishes to represent the natural environment and express the feeling of contentment she experiences when she is in it.

Happy place

For Leila, the mountains are her happy place. “I’d rather go there any day of the week than travel abroad.“

Árbediehtu

One Sámi word that often crops up is árbediehtu – the transfer of traditional knowledge that the Sámi people carry with them without it ever actually being taught. It is a sort of collective knowledge that is borne within the individual. In Leila’s case, it is rather obvious; since she grew up watching people who were always at work and doing crafts, she has inherited it naturally. At the same time, she has a strong will to preserve and pass on certain things that are vanishing, for example, root weaving.

“I had fantastic teachers when I attended the Sámi college, ‘Samernas’, in Jokkmokk. The school has always had great teachers, the kind who really know how to pass on the tradition.

There, root weaving was important for me; not because I wanted to make money doing it, but more because it is an important part of Sámi tradition.”

‘Samernas’

We pause in the new section of Ájtte museum that features duodji to look at a woven root artefact by Ellen Kitok. At first glance, it looks like a sun hat and could well function as one, but it is actually a large sort of dish. A masterpiece, it is a wondrous work of art in which birch root has been tightly woven into a magical basket dish. She has rendered it with astonishing skill, especially when you know how difficult the root weaving technique is and how many hours of painstaking work it takes. During our discussion, Leila frequently mentions the school, which is often simply referred to as Samernas. Does it have great meaning?

“Well, yes, you could certainly say that. Going to Samernas is a bit like compulsory military service; it isn’t a question of whether you do it or not, it’s a matter of when. In our community, there is a before Samernas and an after Samernas.”

Ellen Kitok, mentioned above, has been a teacher at Samernas. A grant honouring Ellen’s mother, Asa Kitok, who taught root weaving, has been awarded annually at the Jokkmokk Winter Market since 2005. The first to win the grant was wood and antler craftsman Jon Tomas Utsi, who taught at Samernas for many years. Root weaver Fia Kaddik, also a former teacher at Samernas, has also won the grant. The transfer of traditional knowledge and skills is not something to be taken lightly. And it has to be done well.

The mountains

Leila hopes to be able to learn more about root weaving. As a student at Samernas, she discovered that the techniques and forms of expression used by Sámi craft artists in the far north differed from those used by Southern Sámi craftspeople. She wants to know why. But when will she find the time? When it comes to work, she already has at least five irons in the fire.

“I work in a very structured way. I let the seasons dictate what I’m going to do.”

Now, during November and December, all of the time must be devoted to the reindeer. The animals must be separated from the large communal herd and identified according to their owners, and it is vital that they reach good winter grazing lands. After Christmas and New Year’s she returns to her studio and produces the art she will exhibit at the winter market. Then comes a period during which she welcomes tourists who come to Jokkmokk to work with their herder dogs. In May, during the calving season, she pulls the plug, heads for the high country and lives the healthy nomadic life. This is a time when she tries to scale down.

“It can be difficult to reach me in May. That’s when I charge my batteries when I’m up in the mountains with the reindeer during calving. It’s probably our most wonderful time of the year. It gives me the renewed energy I need for a trip to Paris or Tokyo, or even to just pick up my phone.”

But what do the mountains mean to her, really? Is it the place or the reindeer?

“I can’t really say if it’s the one or the other. The two go hand in hand. Holistic may sound pretentious, but that’s exactly what it is. It’s all one and the same thing, and we are part of the ecosystem. For me, personally, the mountains are my happy place. I’d rather go there any day of the week than travel abroad. Up there, you get back to basics, the modern world is placed on hold, and you only concern yourself with simple things. Will we catch any fish for lunch? Do we have enough firewood at our camps? There is an overwhelming sense of gratitude for being part of nature, while there is a realization that it is all so fragile. During the calving season, when the new cycle of life is born, everything is so delicate and vulnerable. Nature can wipe everything out with a snowstorm. The modern society can obliterate it all by opening a new mine. All of this beauty is also threatened. It can be so liberating when the simple, day-to-day tasks become most important. Hauling firewood is quite simply a form of mindfulness.”

The Nutti family

Naturally, the reindeer is a central feature in Leila’s art. Her watercolours are not full of abstract explosions of colour; instead, they are more minimalistic and free of embellishment. Otherwise, the Sámi visual expression is often characterized by bold colours. This becomes apparent when you see Ájtte’s new exhibition. Hundreds of incredibly beautiful and colourful woven bootlaces are displayed in a cabinet. How is it that indigenous peoples who have lived so close to the earthy, subdued tones of nature can be so taken by these bold colours?

“I really don’t know. But I have noticed that people from other indigenous cultures throughout the world also like bold, bright colours. I also know that the Sámi were very good at bartering. They were clever hunters who could trade pelts and hides for silver and beautiful fabrics. Then, back in the day, you received the equivalent of a lumberjack’s weekly wage in exchange for a fox fur or wolverine pelt. The hunter held hard currency in his hand.”

Leila tells us that, according to Sámi tradition, a piece of silver jewellery is placed in the crib of a newborn child. Nowadays, young parents hang a silver ring in the child’s baby carriage. Otherwise, the gufihttarat (the underworld people) will exchange the child for one of their own. You might take similar tales with a grain of salt. But I guess many of us here still have Luther on our backs, and the Japanese culture has the word karoshi, meaning death by overwork or job-related exhaustion. In the Sámi culture, the birth of a child was not taken lightly. If you can afford to put a piece of silver jewellery in the crib, at least you can support your family. When Leila Nutti turned 18, her father registered a company in her name. That’s just how things are in the Nutti family. Cultural heritage in a modern form – contemporary árbediehtu.