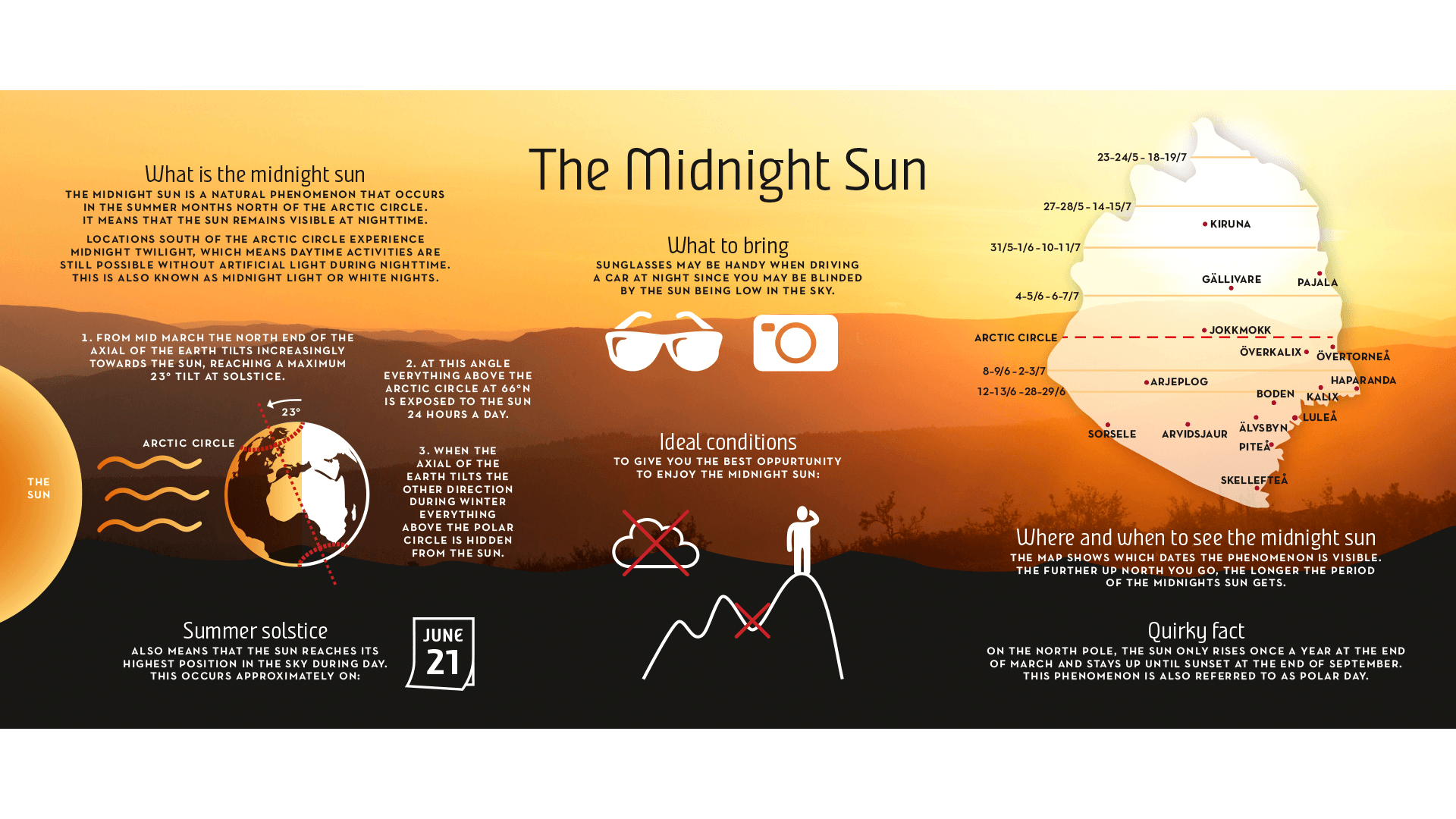

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost point at which the centre of the sun is visible during the June solstice. The summer solstice is the time of the year when the sun is always visible – the sun just never sets. In the northern hemisphere, the summer solstice falls around 21th of June and the farther north you are, the longer is the polar day.

In reality, the Arctic Circle is not an absolute border – you can see the midnight sun as far as 90 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. There is also a slight variation from each year and varies depending on the topography.

Beaivi – the goddess of the sun

In the Sámi language, the sun is called Beaivi, but Beaivi is also the goddess of the sun and has a central place in Sámi mythology. Every year – back in the days – a white reindeer was sacrificed as an assurance that the sun would return after the long and dark winter. At the summer solstice, they tied together rings of leaves and flowers which was put up to honour the goddess. You could find this custom today in the traditional Swedish midsummer celebration – a tradition that might have pagan roots. If there is a historical link between the Sámi custom and the old Nordic, is not known, however.

It is also said that when the sun returned, they prayed for the feebleminded because they thought that mental illness was induced by the long and dark winter. A custom that as we should see, has scientific support, we are indeed affected by the light in different ways, and as a first-time visitor, it can be a challenge to cope with.

Also read

Experience Sámi culture

The goddess of the sun

In the Sámi language, the sun is called Beaivi, but Beaivi is also the goddess of the sun and has a central place in Sámi mythology.

The light and the body

In general, we are not aware of the precision in the timing and coordination of numerous events in our bodies, unless it’s disrupted (most of us know the feeling of being jet-lagged). However, processes as fundamental as the timing of sleep and its coordination with feelings of hunger are a manifestation of numerous physiological and biochemical events that change systematically and predictably throughout the day.

Light is essential for a wide range of non-visual functions: synchronisation of our biological clock, stimulation of human alertness and cognition, memory, reproduction, energy balance, to name a few.

The mechanisms underlying the positive effects of light remain mostly unknown. However, researchers have discovered a new type of light-sensitive cells in the retina of our eyes, called melanopsin. This photoreceptor is thought to relay information about light to non-visual centres in the brain through direct pathways.

THE MIDNIGHT LIGHT

Imagine having a lot more summer. That you never are in a hurry, and always have one more hour to play. The midnight light in Swedish Lapland basically gives daylight for a couple of months, giving you all the time you need to slow down and see the world.

The Suprachiasmatic nuclei – our master clock

Hypothalamus is part of the limbic system, a system of the brain that is involved in the regulation of a variety of fundamental and essential functions of the body. The hypothalamus as such is a small almond-sized structure involved in functions such as thermoregulation, blood pressure, heart rate, arousal, energy balance, memory, and sleep.

The suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) is a small region in the hypothalamus, responsible for controlling circadian rhythms, which is an oscillating biological process that helps us establish a sleep pattern – our master clock.

The retina of our eye consists of rods and cones responsible for vision. Still, the retina also contains photoreceptor cells that project directly to the SCN in the hypothalamus, thus providing information about light and dark.

Through different pathways, the SCN then control the release of various hormones such as somatostatin, oxytocin, and melatonin from structures as the hypophysis and the pineal gland as a response to the incoming information from the eye as well as the interpretation and expression of specific clock genes in the SCN.

When the sun goes down, melatonin (and other hormones) is released as a signal that it is time to head to bed. But what happens if the sun doesn’t go down?

Adaptation among Arctic animals

Researchers at the University of Tromsö has found that some Arctic animals such as the reindeer show circadian rhythms only in the parts of the year that have variations in brightness between night and day. The researchers could see seasonal changes in foraging, metabolic activity, and power of diel and circadian rhythmicity; effects that could be viewed as adaptations to the extreme living conditions in the high Arctic.

However, this is not the case for humans. So even for the inhabitants of Swedish Lapland and the other Arctic regions, sleep deprivation could be a problem so how could we cope with the midnight sun and what can we do to maximise our beauty rest?

The solution

It’s quite easy, actually. We need to reduce the light reaching our eyes. That could be done wearing sunglasses during the most intense light and use thick curtains in your bedroom – it should be as dark as possible so the photoreceptors in your eyes could signal to the suprachiasmatic nuclei, which in turn tells the pineal gland to release melatonin, which makes us sleepy. Easy, right?

A good tip could be to bring a sleep mask, but to be honest – who travels to Swedish Lapland to sleep through those fabulous lukewarm nights? Our best recommendation is for you to get out and experience one of the wonders of nature we can offer in Swedish Lapland. To sit and relax and grasp the beams from the sun that will never go down behind the horizon is pure magic.

100 days without night

The season with midnight light in Swedish Lapland is around 100 days long. You play golf in the middle of the night, and you take a swim when you feel like it and those who have never experienced the midnight light before wonder how they’ll ever manage to sleep. But then you make your mind up not to worry about sleep and decide it’s time for further adventures — even more summer.