The University of Uppsala was partly funded by profits from the salmon fishing in Edeforsen rapids (near Harads and Treehotel) in the Lule River. The profits from salmon fishing were also used to found the city of Luleå. In fact, up until the 20th-century, salmon, not steel, was Luleå’s main source of income. In 1949, 110 tonnes of salmon were caught in the river. These days you’ll probably want to head to the Byske, Kalix, Torne and Vindel Rivers instead, even if the fishing is good downstream from the Bodforsen rapids.

Fishing journalists often refer to the Arctic char as ‘the Greta Garbo of the mountains’. Partly because of its beauty and partly because of its temperament. There’s no other fish that can make mountain fishing go from one extreme to the other the way this Lady Camellia does. One second it bites anything. The next, there’s absolutely nothing you can tempt it with. Among chefs, the Arctic char is a sought-after table fish. It’s a little bit fattier than other salmon species, and therefore there’s less risk of it becoming ‘dry as a bone’ when you fry it.

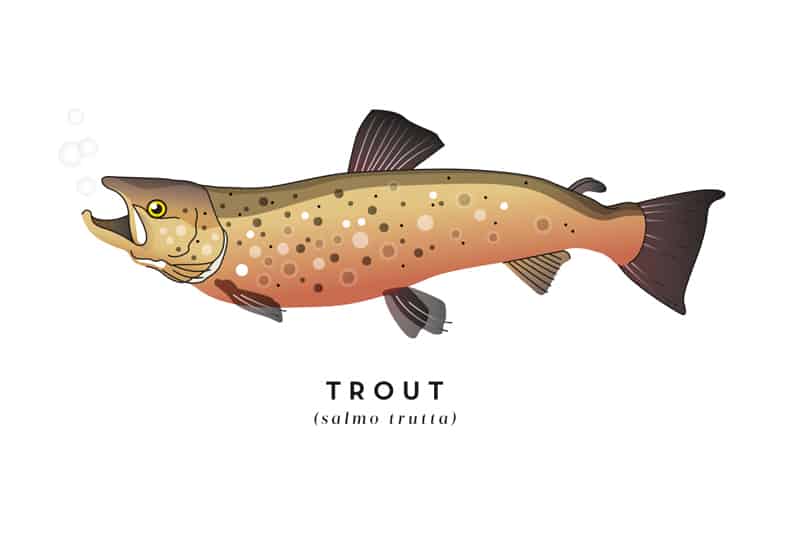

A sweet-water chameleon and almost every sport fisher’s dream. The trout can adapt to all kinds of environments as long as the water quality is good. There’s the anadromous, or sea-run, kind that spends its life in the Baltic Sea and then rises up the rivers to spawn. There’s the brown trout version that stays in small bodies of water and just adapts its size to its habitat. And there’s the version that lives in lakes and runs up the rivers to spawn during autumn, and they can get as big as you’d like. The known Swedish record, 17 kilos, is from a lake in Swedish Lapland.

It’s said that the grayling gets its Latin name from smelling vaguely of thyme when it’s caught. The large, shimmering dorsal fin – often known as ‘the sail’ among sport fishers – is the grayling’s distinctive feature. And it’s also a real mood enhancer for us fishers because there’s always a grayling in the mood for a bite. And if you find one, you’ll find several. Grayling live in shoals. It’s present all over Swedish Lapland, from the sea to the mountains. A one-kilo grayling is a trophy, but many weighing in at over two kilos are caught every year.

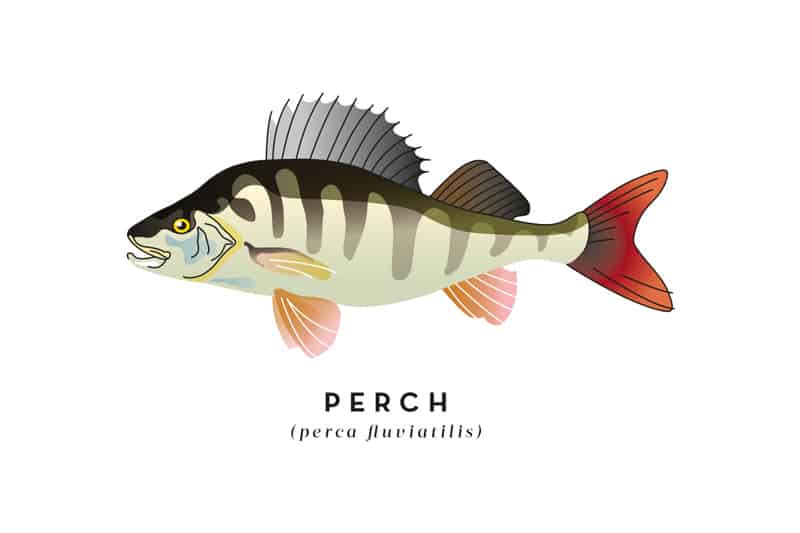

Perch skin was used when making coffee back in the day and referred to as ‘sieve skin’. People used to sieve coffee through a perch skin to separate the grounds from the coffee. Enok Sarri in Nikkaluokta would predict the weather using reindeer stomachs and perch fins. Another weather teller, Jean Jönsson, remembers how all perch fins were black during autumn 1965. That winter was unusually cold. According to legend, the perch got its name when Saint Peter lost his key in a lake where the perch lived. When the perch refused to bring the keys back, the other fish got upset and beat the perch until stripes appeared. In reality, the perch usually take the bait. The Swedish record is 3.15 kilos, but anything over a kilo is a nice trophy. The perch is also a really tasty table fish.

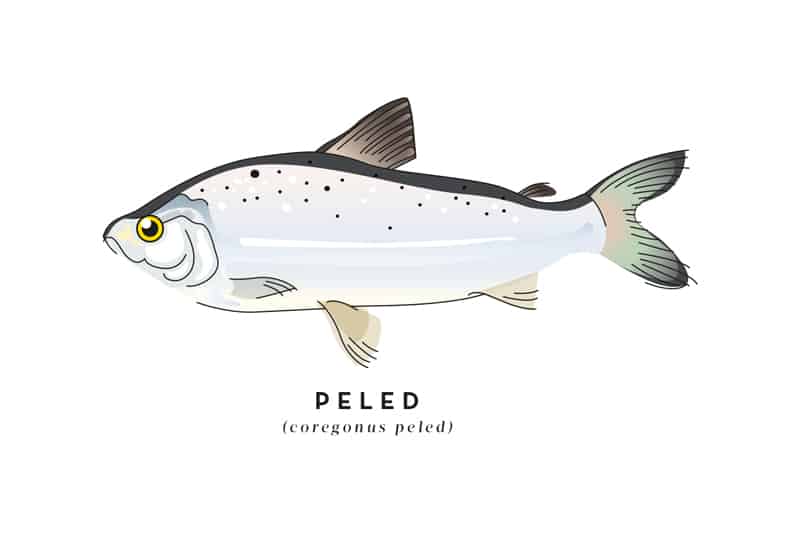

In Lake Storvindeln, along the Vindel River, there is a unique fish: the peled. It used to be classified as a variety of whitefish, but the morphological difference is considerable. For example, its eyes and mouth are larger, and it has an extreme amount of gill rakers. Even if this ‘original whitefish’ is acutely threatened, it’s more or less unknown. Researchers used to believe it had relatives in Siberia, but that’s not the case. Classic whitefish, which is a wonderful table fish, provides us with a spectacle on the long piers of the Torne and Kalix rivers when it’s fished out using bag nets. Whitefish is always present in the Kukkola cultural village, in the rapids as well as on the menu.

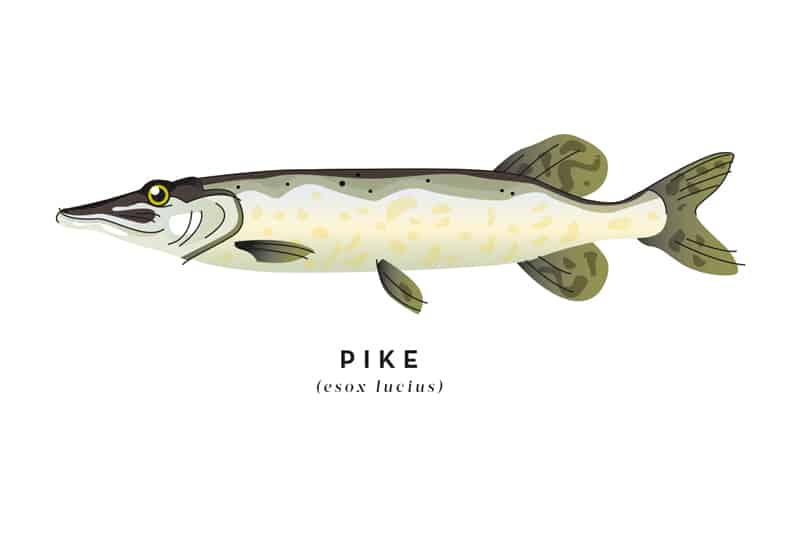

The Russian author Sergei Aksakov wrote: “The greediness of pike knows no bounds”. It’s not surprising that we call them crocodiles. It often bites fish too large for it to swallow; its greed literally kills it. The current Swedish record is 21.07 kilos, but many pikes have been caught and weighed in at more than 20 kilos, but the methods of catching them or the weighing procedure have been questioned. Among other stories, rumour has it that a 30-kilo pike was once caught in Lake Hornavan in Arjeplog. The female is the larger version of these crocodiles. Very few male pikes reach ten kilos. These days it’s more common to measure the length of the pike instead of the weight because more and more anglers practise catch and release and put their pike back. A one-metre pike is a trophy.

The most common fish in Sweden, yet a species that almost no one recognises because they think it’s something else. Perhaps the fry or young fish of another species. The minnow is known by many different names in Sweden: elritsa, kvidd, alkuva, alkutta, alekula, alkura, kur, äling, sabbik, elling, glirr, gli, blindsill, budd, hundgädda, iggling, im, kvidd, laxbådd, lortbuk, mjolpus, mudd, myrsik, spragg, stensil, görkänga, skinnfisk, plump, agn, ölkytt and örkytt. Next time you go for a swim and see fish that are 6–8 centimetre long in the water around you; they’re probably minnow.

A latecomer in Swedish Lapland. Or, perhaps a kind of research ‘Gulag’. The species – sometimes spitefully referred to as ‘pike trout’ – was introduced to the large mountain lakes to eat small fish. According to researchers, they wouldn’t be able to breed well in these new waters. But the new species didn’t care much about either assumption. The stock of smaller fish hasn’t been that affected, and the lake trout are multiplying. World-leading research is carried out in Ammarnäs by the University of Umeå. And many trolling fishers find their challenge in the hunt for the lake trout.

As a sport fish, perhaps it’s not worth mentioning, but it’s very special as an individual. It’s a kind of matriarchy in the northern Baltic Sea. Or rather – a fish subject to gynocracy where the females are worshipped for their roe, and the males might at best be salted and barbecued on a gridiron over an open fire. Vendace roe from Kalix became Sweden’s first product with a protected designation of origin in 2010, on a par with Champagne and Parmesan. And if you ask us, it goes well with both, and with much else besides.